I have written about Revit Macros in the past. To this day, it is my favorite way of scripting in Revit.

When I was starting with Revit Macros for the first time, I was inspired by the idea of being able to apply my growing knowledge of programming directly to the tool I used the most in my Architecture practice. The amount of material that was available for the topic was also a great help – giants like Jeremey Tammik and Harry Mattison have paved the way together with many other brilliant minds making it really easy for a beginner like myself to get a basic script up and running.

However, as a self-starter with no one around to ask, it was the simple things I would trip over, wasting unreasonable amounts of time. I would try to copy one of the ‘ready-to-use’ samples I found online, I’d hit F8 to compile the code, the red, squiggly lines would pop-up and my heart would sink. One of the most frustrating feelings in the world must be having Google and not knowing what to type in it. I’ve seen the same questions I’ve asked myself so long ago in forums and tweets. Here I have summarized the 3 concepts I wish someone explained to me back in my toddler days.

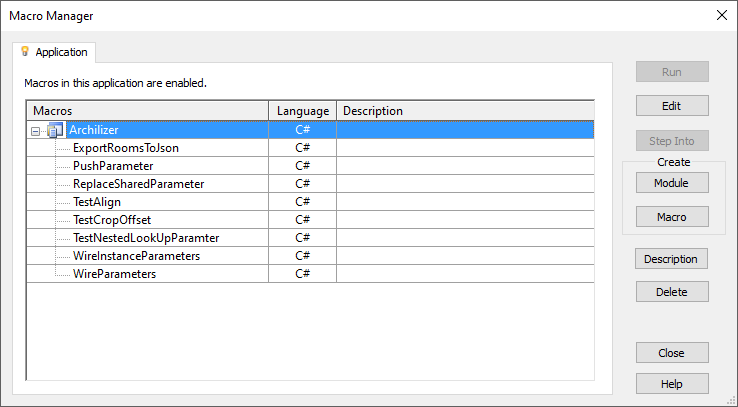

#1 Application vs Document

This is the first very concept that I needed to get drilled into my brain. Obviously, the difference is that the Application is the Revit (application) while the Document is the Project, duh. Let’s say that again:

Application = Revit. When you open Revit, there are no open Documents, right? Right. You need to open one yourself before you even start working, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that the Application can exist quite happily on its own without any Documents being opened. And indeed, you can run a Macro in the context of the Application with no Document being opened, although I cannot think of a good example for one right now.

Document = Project. Regardless of the type and location of the document (family or project document, workshared or not, local, network, or cloud-based) now you are playing on the level of the Document.

Which one is better? Sidenote

Now that we understand the concept behind each one and how to use them, I will give you my personal way of working with Macros. Always write Application Macros, it’s really that simple. As a Consultant, I am rarely with a project for more than a couple of months while at the same time I am constantly juggling between several projects and in many different organizations. I need to move around computers quite often too, and you might think “Well, isn’t it better to create a single document that you travel with on your jolly trip which contains all your Macros handy?” and you might be right, but I just hate it how clunky it is when migrating Document Macros.

This, coupled with the ability to write whatever short script I need on the go plus the added benefit of storing my work via Source Control, which I will discuss a tad bit later, makes me use Application Macros 100% of the time. If I remember correctly, there was only one time I found this difficult to implement. I was facing an Application level restriction because of Admin rights which prevented me to create the Application Macro Module to start writing macros. I don’t know if that’s still a thing, but in case you stumble on it, please let me know what the circumstances were – I would like to add it to the massive list of pet peeves I have with IT support in the context of our industry.

So, why does it matter?

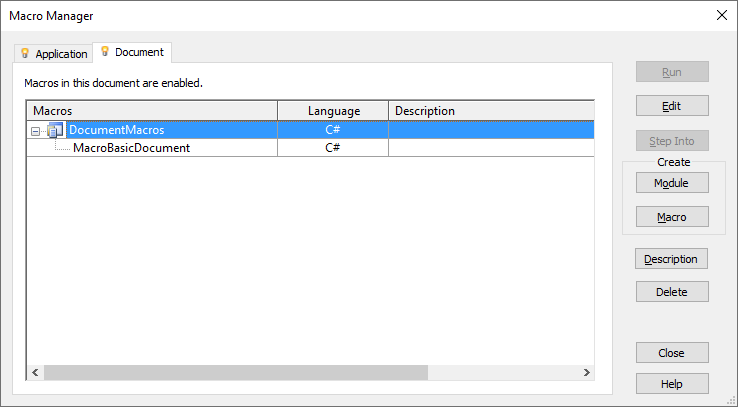

Knowing which type of Macro you are working in is also crucial when trying to re-use code from the Internet. The reason is that a Document macro will have a different way of instantiating the Document object than the Application macro. And the Document object is the key ingredient to most of your scripts. Knowing how to get a hold of it in the two different contexts is very important.

Above you will notice the use of the reserved word ‘this‘. In object-oriented programming, ‘this‘ refers to the context that you are running your code from. Said differently, you are asking the question ‘who am I that’s running this code?’ In the context of the Application, I am the UIApplication. This is the top-most instance that you can get (as far as I understand it). The UIApplication has reference to the Application and the UIDocument, and the UIDocument has reference to the Document itself. (If there is no Document opened, the UIDocument will be null).

When we are working from within a Document Macro, the “I” is the DocumentMacros.ThisDocument object. I suppose this is a special class that deals with Document Macros and I haven’t seen it used elsewhere. Still, the important bit here is that the DocumentMacros.ThisDocument has the reference to the UIApplication (this.Application). Now that we have found the top-most object, we can go back to the previous example and find the Application, the UIDocument, and finally the Document.

To sum up – if you are getting an error when compiling your Macro, make sure you are using the correct way of referencing the Document.

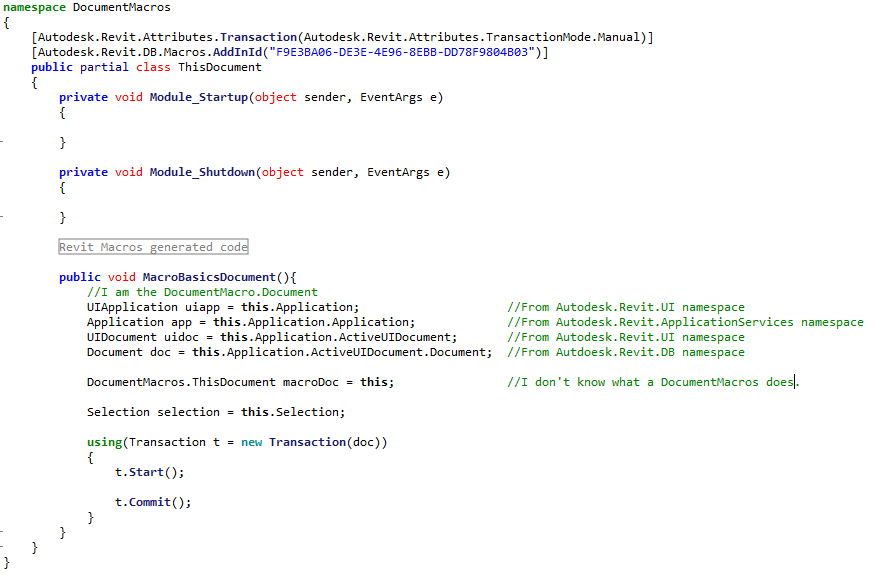

#2 Namespaces

When we say DocumentMacros.ThisDocument we are really saying ‘I want to use the “ThisDocument” class from the “DocumentMacros” namespace’. If you pay closer attention to the start of your Macro page, you will see a bunch of ‘using’ statements. Those statements are references to different Namespaces which we would like to include. You will also notice that the whole body of code is wrapped in a block starting with ‘namespace DocumentMacros{}’.

Time to dumb it down – what is a Namespace? Well, you know how when you write code, you start with a bunch of lines. Then you write some more. Then you keep writing and writing until your code becomes completely unwieldy. Obviously, there is a way to organize code. With no respect for the different functionalities of the elements I am about to describe below, in hierarchical order, in C# we use the following levels of the organization to help us solve this issue:

- variables

- methods

- classes

- namespaces

- assemblies

If you are a professional programmer, just go away right now as I am ashamed of my oversimplification.

Each Macro is a method. When you type ‘public void TagAllRooms() { }’ you are creating a method (void) that is public, visible by Revit (you can make it private for internal use) which does something.

A collection of Methods is a Class, just like a collection of Classes is a Namespace, just like a collection of Namespaces is an Assembly. A class can have a single method just as a namespace can have a single only class, but that doesn’t change the way the organization works. The assembly, the higher-level of the hierarchy, is effectively a library of sorts, oftentimes it complies in a .dll file. People create these libraries to lock-in highly useful and reusable classes and methods. Those libraries are then easy to distribute around for the benefit of the many.

The way to use those libraries is through References.

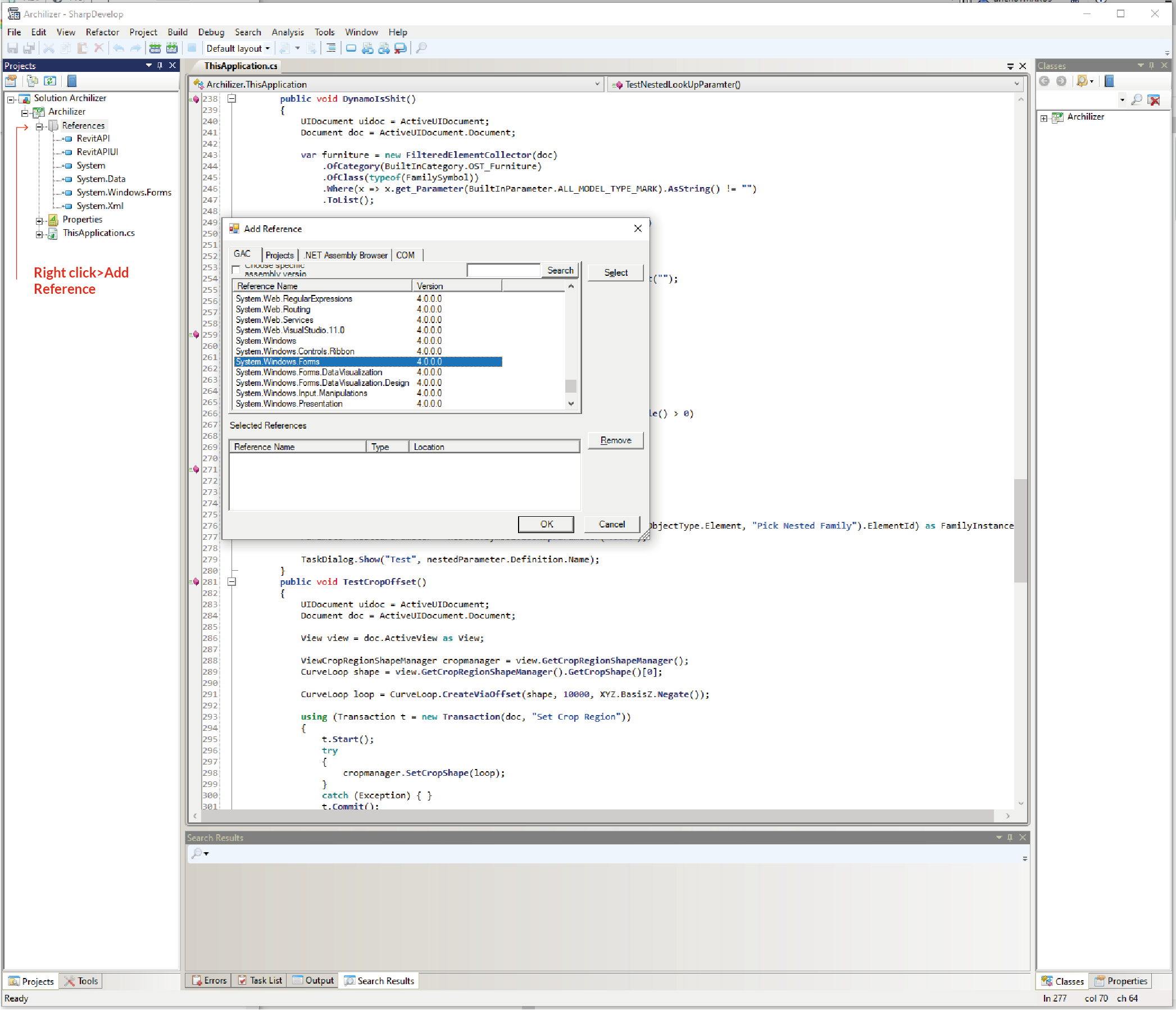

#3 References

Another dead-easy trip-over for me was understanding and using References. As we said, references to existing libraries are very useful and common ways to not reinvent the wheel in the world of Programming. Invariably, you are bound to run into a scenario where the code you are trying to work with relies on one or many such references. It drives me crazy when I can’t figure out where such references are taken from. If there are no explicit directions in the code, it’s sometimes quite difficult to know what to do.

But most of the time, what you need to do is simple – head over to the left-hand side of the SharpDevelop window and right-click on References. Scroll down until you find the name of the library (usually coincides with the Namespace that it contains) and add it to your code. Try rebuilding and if that doesn’t solve it, make sure you are using the namespace at the beginning of your Macro.

Sharp Develop is an IDE

Although knowing this is not vital for your survival, I personally wish I found the answer to this question earlier. If your background is not in programming and you are just joining the show, you will be hearing about IDE.

IDE stands for Integrated Development Environment. Which is like saying that a car is a vehicle with an internal combustion engine. o.O Here is my dumb interpretation of what an IDE is – you know how Photoshop is good to edit photos? Or Word for documents? Excel does tables, right?

Well, programmers use different IDE packages to write and edit their code. Sharp Develop is one of them and you use it, seemingly from within Revit, to create Macros. There are other IDEs just as there are other tools that are similar to Photoshop (I’m sure they must exist). Visual Studio, Atom, Sublime Text, Notepad++, although unique in their own way, do just that – write and edit code.

Source Control

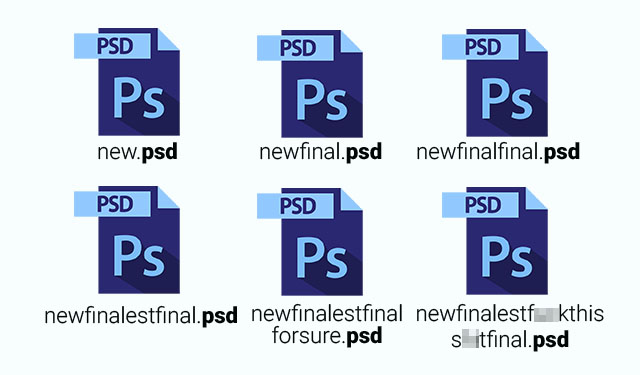

Source Control (or Version Control) is the practice of tracking and managing changes in code. If you are familiar with this popular meme you will intuitively know what source control is all about.

In praise of Revit, the ability to work off a Central file has forever changed the way we approach our work – I personally think that every single program in the world should have the ability to allow collaborative work on the same file forever and ever with inbuild version control, Amin.

What does that have to do with Macros, you ask? My solution to migrate macro work through the years is a single Github file that I dump macros I find worth keeping. The file is now 7000 lines long and growing. I haven’t really been neat and tidy with it. But I can still find snippets of code to reuse when I have to. This process is not scalable or company-wide applicable. But then again I don’t think Macros are the most user-friendly way of deploying scripting either. My way of keeping track in Git matches the hacky-style of writing quick Macros and I am happy with it.

The future for Macros

I’ve been using Revit Macros for about 5 years now. I still find it to be the quickest way to get a computational workflow going. Macros were probably the reason I never got that engaged with Dynamo. (In spite of its obvious advantages – community effort, reusability). Finally, we (Arcihlizer) are now migrating most of our Macros onto pyRevit. I wouldn’t go more into pyRevit right now as we are planning a series of posts around it. But boy am I impressed by the amount of smartness that went into making this platform! Ehsan Iran-Nejad is an amazing human being as far as I can tell.

I see pyRevit as a great platform to share our work. Translating the most useful portion of our in-house scripting is on the agenda. That said, Macros are still my go-to solution to do scripting inside Revit. They are also an amazing way to start applying scripting to do actual work. And if you are a beginner with scripting, I can whole-heartedly recommend picking them up!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?

Feel free to contribute!